It has been over two months since I last posted. In that time…

- I attended the Opening and Scientific Symposium for the launch of the KwaZulu Natal Research Institute for Tuberculosis and HIV (K-RITH), a groundbreaking collaboration between the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and University of KwaZulu Natal, which is housed in a world-class laboratory facility at the UKZN Medial School campus. As a Caprisa fellow, I am lucky enough to sit in the K-RITH building! The energy and scientific rigor presented at the K-RITH symposium was inspiring, with a wide range of presentations, including Bruce Walker, Eric Goosby, Tony Fauci, and Nobel Prize laureate Peter Agre.

- President Obama was re-elected (!!), which allows the global health community to sigh a breath of relief and get back to work. Center for Global Development has mapped the top five global health items that should be on the President’s agenda over the next four years.

- Proposition 37 was defeated in California by 53.1% to 46.9%. The ballot measure, which was bankrolled by $47 million in campaign contributions from biotech companies such as Monsanto, would have made California the first state to require labels on foods containing genetically modified organisms. This disappointing result marks a major setback for the food movement.

- The Phase III trial of the RTS,S malaria vaccine showed only 31% efficacy in children, disappointing results after the Phase II trial results showed higher efficacy.

- UNAIDS released its Global Epidemic Annual Report, which details an increase in the number of people worldwide on antiretroviral therapy and a decrease in new infections. However, the pace of ART scale-up does not match the decrease in HIV incidence, with 2.5 million people becoming newly infected last year, while only 1.4 million received treatment for the first time.

- Hurricane Sandy devastated the Eastern seaboard.

On a personal level…

- I applied to graduate school (!!)

- I signed up for my first marathon (!!)

- I planned my boyfriend’s trip to South Africa and have watched the countdown go from 97 to 33 days (!!)

Today is Thanksgiving, a uniquely American holiday. I am living thousands of miles away from my family and the traditions of Thanksgiving that I grew up with and endlessly adore.

It’s funny how Americans living abroad instinctively seek each other out in late November–they crave the company of other Americans, the taste of Turkey and mashed potatoes, sounds of football on TV and in the backyard. But the values of Thanksgiving are universal–being thankful for family, friends and health. Family, friends and health relate to each other in such important and interconnected ways, and nowhere is that more clear than in Durban, South Africa.

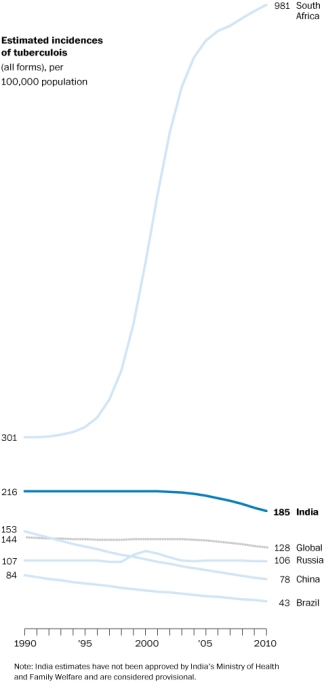

Take TB for example, which correlates highly with HIV infection. South Africa has a 70% HIV/TB co-infection rate. Both TB and HIV are closely related to your social network: how many sexual partners you have, whether you are using a condom, being faithful, what type of work environment you’re exposed to, and the list continues. Your health and well-being is then again intricately related to your friends and family and the support they provide you in your care and treatment. Whether you are willing to disclose your HIV status to your partner is a powerful indicator for your treatment success or failure and loss-to-follow-up. Friends, family, and health (and in the South African context, community as well) reinforce each other in positive and negative ways through a powerful feedback mechanism. Any response to TB or HIV must consider the social and behavioral factors** that drive the epidemic.

Tonight I will feast on local sweet potatoes and butternut squash (yes, there will be Turkey, but I am a vegetarian) in a truly South African Thanksgiving. When I look around the table, I will see my South African family, made up of beautiful faces I have come to love. We will carve new Thanksgiving memories and traditions that will live on in the Durban soil.

**For post food-coma reading, check out the Center for Global Development’s publication by Saugato Datta and Sendhil Mullainathan on the ways that behavioral economics can and should be used to inform better policy design.

The development a vaccine, while progressing, remains in the very distant future, for reasons that only a real scientist can articulate. There are some exciting and game-changing tools such as microbicides and other forms of pre-exposure prophylaxis on the horizon with the potential to dramatically alter the shape of the epidemic and change the gendered power dynamics that fuel the epidemic.

The development a vaccine, while progressing, remains in the very distant future, for reasons that only a real scientist can articulate. There are some exciting and game-changing tools such as microbicides and other forms of pre-exposure prophylaxis on the horizon with the potential to dramatically alter the shape of the epidemic and change the gendered power dynamics that fuel the epidemic.