ALAN WHITESIDE AND JAMIE COHEN

(as seen in The Globe and Mail)

On Nov. 28, Parliament sent a deafening message to the world about the value it places on global health. Bill C-398 aimed to make the Canadian Access to Medicines Regime (CAMR) easier to apply. The CAMR is a mechanism for providing generic drugs to the world’s poorest countries. It is so complex that it has hardly been used.

The bill was defeated and this means there will be fewer lives saved and more new infections. It presented an opportunity for change: This has been lost.

Antiretroviral (ARV) drugs allow HIV-infected individuals to have long and healthy lives; without them, illness and death are virtually inevitable. Over the past year, it has become apparent the drugs also help prevent transmission and are a key part of the armamentarium for halting the AIDS epidemic. Since the development of highly-active antiretroviral therapy was announced in Vancouver in 1996, drugs have become cheaper and more effective.

Global precedent has been set around the ability to lower the price of ARVs through direct negotiations and innovative financing mechanisms, such as the Medicines Patent Pool. In July of this year, the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), with generic drug manufacturers, announced price reductions of up to 30 per cent. This brought the cost of tenofovir-based regimens down to $125 per patient per year in the 70 CHAI procurement countries.

Access to low-cost ARVs is critical for health care in developing countries, many of which depend on foreign aid for health funding and drug procurement. Tanzania, for example, receives 49 per cent of its health-care funding from abroad. Of Malawi’s $558-million health funding for 2012-2013, the Ministry of Health provided only $132-million (24 per cent).

ARV price reductions help developing countries take greater financial responsibility for drug procurement and graduate from donor dependency. These investments are essential to save lives and will bear fruit in the future: healthy populations are crucial for sustainable growth and development.

On this World AIDS Day, on the heels of US Secretary of State Clinton’s release of the Blueprint for an AIDS-Free Generation, there is a renewed sense of optimism. We believe we are at a turning point in the 31-year epidemic. Science has delivered the tools and knowledge and will continue to develop new technologies. The biggest obstacle is implementation.

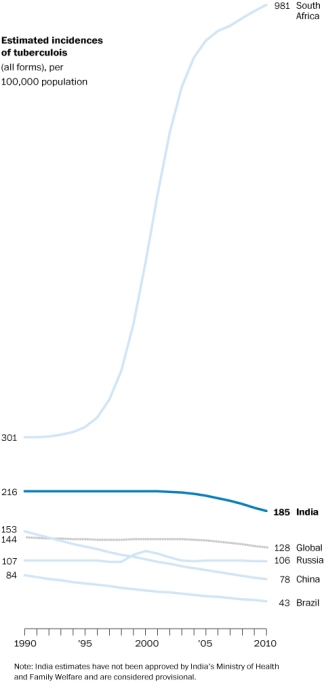

In our country, South Africa, which runs the world’s largest treatment program, only 58.3 per cent of eligible adults and children are receiving ARVs. In 2010, with help from CHAI, the Department of Health was able to negotiate a 53 per cent price reduction in drug prices, saving almost $250-million. This will enable South Africa to reach its treatment goals.

The defeat of Bill C-398 could have broad and far-reaching implications for global health delivery and particularly for HIV and AIDS. It may signal a shift in the momentum towards ‘ending the epidemic’ that began at the International AIDS Conference in July, 2012, in Washington, DC. All people everywhere deserve access to lifesaving treatment and care. Sadly this is now more difficult to achieve.

The development a vaccine, while progressing, remains in the very distant future, for reasons that only a real scientist can articulate. There are some exciting and game-changing tools such as microbicides and other forms of pre-exposure prophylaxis on the horizon with the potential to dramatically alter the shape of the epidemic and change the gendered power dynamics that fuel the epidemic.

The development a vaccine, while progressing, remains in the very distant future, for reasons that only a real scientist can articulate. There are some exciting and game-changing tools such as microbicides and other forms of pre-exposure prophylaxis on the horizon with the potential to dramatically alter the shape of the epidemic and change the gendered power dynamics that fuel the epidemic.